Why the NIH's Future Matters to Everyone

This week, federal health communications were shut down, NIH study sections canceled, and the future of the NIH called into question. Why the NIH matters to everyone and how we need to move forward.

This week, the Trump administration implemented significant restrictions on federal health agencies, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH). These restrictions included cancellation of meetings, a communications pause, a freeze on hiring, and an indefinite ban on travel. From what I can tell, internally, the NIH is in chaos. Some NIH program officers have halted email communications with investigators, while others appear to be doing business as usual. In addition, the Trump administration appointed Dr. Matthew Memoli, an NIAID researcher as acting director of the NIH. Dr. Memoli has been outspoken in his criticism of former NIAID director Dr. Anthony Fauci. President Trump’s pick to lead the agency is Dr. Jay Bhattacharya, a physician and professor at Stanford University, although confirmation hearings have yet to be set.

In the meantime, the new communication directives led to the cancellation of scientific meetings, some of which were scheduled to review grant applications. This means that investigators who spent months or, in some cases, even years preparing funding applications are now left in limbo.

The delays in critical public health communications also included the CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, a key resource for public health professionals across the country. Updates on the spread of bird flu were expected in that report. Former CDC director Dr. Tom Frieden mentioned on X that the MMWR has been published weekly without pause since 1960, until now.

The turmoil has left NIH employees and researchers funded by the NIH in distress. Reactions within academic circles range from mild to concern to full-blown panic. Other executive orders have raised even more alarm. This includes the executive order directing federal agencies that the policy of the United States recognizes only two sexes, male and female. The word “gender” must be replaced with “sex” throughout federal policies. This brings into question whether research involving people who are transgender, gender fluid, nonbinary, or otherwise gender minorities will continue to be funded. The executive order declaring DEI programs “illegal and immoral” is also causing significant concern to many researchers, as tackling social determinants of health has been at the forefront of many recent academic discussions and funded NIH research programs. These are the kinds of initiatives that ensure we understand the factors that lead to health and disease across our entire patient population.

Even before the events of this past week, there have been significant doubts about the future direction of the agency. During the last congress, several legislators developed proposals to make significant changes to the NIH. This includes two separate proposals from then-House Energy and Commerce Committee Chair Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-WA) and then-Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee Ranking Member Bill Cassidy (R-LA). Cassidy’s white paper was more of a framework than a formal proposal. But McMorris Rodgers proposed more sweeping reforms, including a plan to reduce the number of institutes from 27 to 15, although the overall budget would remain intact.

On the one hand, yes, many would agree some reforms are overdue and could help to speed up the progress of research. Some of the proposed changes include things like term limits for key NIH positions, which is good practice for any organization. The NIH is far from perfect. But at the same time, it is also indispensable. We must not throw out the good with the bad. The NIH doesn’t just power groundbreaking discoveries—it saves lives, strengthens the economy, and cements the U.S. as a global leader in science and innovation. Its future impacts all of us.

How the NIH Powers Medical Progress

The NIH isn’t just a research institute—it’s the beating heart of medical progress for the entire globe. For decades, it has been the foundation of some of the most transformative breakthroughs in science and medicine. Its work extends far beyond the labs at Bethesda, Maryland, touching hospitals, clinics, and homes across the world. The NIH’s unique mission is to support basic and clinical research that often doesn’t attract funding from private industry. These investments have paved the way for some of the most impactful advancements in medicine—innovations that would otherwise never have been possible.

The NIH serves as a global beacon of scientific excellence, setting a gold standard for biomedical research and innovation that is admired, emulated, and revered by scientists and research agencies worldwide. The NIH serves a vital role not just by funding research, but also by creating research communities that are vital to the development of future scientists and the health of the investigative discourse. The NIH also plays a vital symbiotic role with academic healthcare institutions. If you’re seeking world-class healthcare, the best place to look are academic institutions. NIH-funded physician-scientists who work there typically are the top experts in their respective fields because they have dedicated time for research to focus on highly specialized areas of medicine and are routinely sent the most challenging cases. If you have an undiagnosed condition, a rare condition, or need access to experimental therapies through clinical trials, this is where you need to go. Without the NIH, these health systems and the kinds of doctors who staff them will no longer exist.

Just to remind ourselves, this is just a small list of NIH-funded breakthroughs:

COVID-19 mRNA Vaccines: The vaccines that saved millions of lives during the pandemic didn’t come out of nowhere. Decades of NIH-supported research laid the groundwork for mRNA vaccine technology. Now, that same technology holds promise for vaccines against HIV, cancer, and beyond.

Decreasing deaths from heart disease: Arguably the most important epidemiologic study ever conducted, the Framingham Heart study, has led to massive declines in cardiovascular deaths in the last 75 years. This crucial NIH funded study, laid the foundation of understanding for the role of hypertension and cholesterol that led to life changing medicines that have since been developed.

CRISPR Gene Editing: While the NIH didn’t directly fund the invention of CRISPR, it was developed by Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier, whose groundbreaking research on RNA and bacterial immune systems was supported in part by NIH funding and laid the foundation for this revolutionary gene-editing technology. Since then, the NIH has significantly accelerated further development and advancement of CRISPR through programs like the Somatic Cell Genome Editing (SCGE) initiative, which has allocated millions of dollars to improve genome-editing tools and expand their therapeutic applications for diseases such as sickle cell anemia, cancer, and neurodegenerative disorders.

The HPV vaccine: The NIH significantly contributed to the development of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine. Researchers Dr. Douglas R. Lowy and Dr. John T. Schiller at the NIH’s National Cancer Institute (NCI) conducted pivotal studies on HPV’s molecular biology. Their work led to the creation of virus-like particles that form the basis of the HPV vaccine. This foundational research was instrumental in the vaccine’s development which prevents cervical cancer and other cancers caused by HPV. Widespread use could one day eradicate cervical cancer entirely.

This list could go on, but you get the point: the NIH makes discoveries that save lives.

NIH Research: Fueling the Economy and Setting a Global Standard

Talking dollars and cents, in FY 2023, the NIH had a $47 billion budget. That’s a big number, but here’s what’s bigger: the NIH generated $92.89 billion in economic activity that same year. For every dollar spent, the economy saw a $2.46 return. This funding supports more than 300,000 researchers across 2,500 institutions in the U.S., driving innovation in biotech and healthcare. The ripple effects are enormous—new patents, companies, and industries.

The NIH’s impact isn’t limited to the U.S., either. Agencies around the world—like the UK’s Medical Research Council (MRC) or the EU’s Horizon Europe—often align their research priorities with the NIH’s. The scale of the NIH’s funding and its ability to bridge basic science and clinical application set it apart as a global leader.

Agreed, the NIH Isn’t Perfect

For all its accomplishments, the NIH admittedly has areas that need improvement. One of the most persistent criticisms of the NIH is that its funding tends to flow to a select group of researchers and institutions. Large, well-established universities often receive the lion’s share of grants, while smaller institutions are less able to compete. This dynamic makes it especially tough for researchers at less-resourced institutions to compete, no matter how innovative their ideas may be.

Part of the reason for this is that applying for an NIH grant is a notoriously time-consuming and complicated process. Preparing a single application can take months, requiring exhaustive documentation, detailed budgets, and pages of justifications. To put applications together like this requires time, staff and infrastructure, which smaller institutions often have less of.

The NIH’s funding culture also tends to favor low-risk, high-certainty projects. This means proposals with a high likelihood of success—often incremental advances in well-established areas—are far more likely to be funded than bold, high-risk ideas that could lead to groundbreaking discoveries. Researchers sometimes joke the bar for preliminary data is so high that projects need to be mostly completed before they’re even submitted for funding. High-risk, high-reward programs like the NIH Pioneer Award exist, but they’re relatively rare and don’t address the broader culture of caution that dominates the agency.

The peer review process for funding proposals was designed to ensure the quality of NIH-funded research. But in practice, implicit biases can also creep into the process, perpetuating inequities in funding outcomes. Peer reviewers, being human, may bring personal frustrations—like their own past rejections—into the process, leading to overly critical assessments. Reviewers, who are essentially volunteers, are often overburdened with applications, leading to rushed evaluations or superficial critiques. This system favors polished applications from well-supported labs over raw but promising ideas from less-resourced applicants.

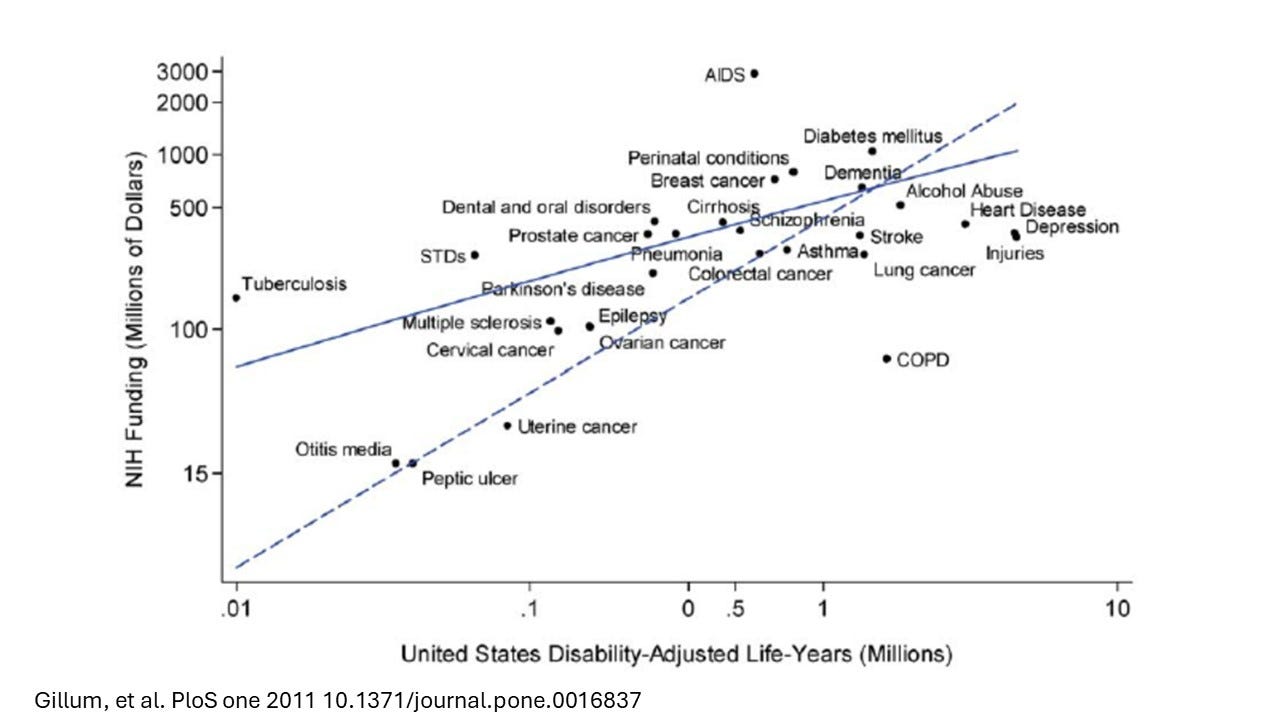

Some of the criticisms directed at the NIH relate to funding priorities and the need to better align with public health priorities. The interesting thing is that if you look at the historical relationship between disease burden for some of the major disease categories funded by the NIH measured in disability-adjusted life-years and NIH funding, you’ll see that save for a few exceptions, there actually is a rather linear relationship between NIH funding and disease burden. The majority of money really has historically gone towards diseases in relative proportion to their impact on Americans.

What Could be Next? Building a Better NIH

The path forward shouldn’t be focused on tearing the NIH down— rather we should be focused on building it up. How can we invest to make it even better? While there are multiple ideas to consider, here are a few thoughts.

One way to ease the burden on researchers would be to simplify the grant application process. For instance, instead of requiring exhaustive proposals from the outset, the NIH could implement a tiered system where researchers submit brief concept papers first. Only the most promising ideas would advance to the full application stage, saving time and effort for applicants and reviewers alike.

The NIH should also expand funding mechanisms for high-risk, high-reward projects. Programs like the Pioneer Award are steps in the right direction, but they remain limited. Increasing funding for bold ideas, even those likely to fail, could pave the way for breakthroughs that traditional funding models often overlook. Complementing this, de-emphasizing the reliance on preliminary data in grant reviews would give early-career researchers and those tackling novel ideas a fairer shot, leveling the playing field and rewarding creativity over predictability.

Diversification of study sections to include early-career scientists, underrepresented groups, and experts from broader fields could reduce groupthink and bring fresh perspectives to the review process. The NIH could also improve transparency and collaboration by incorporating real-time reviewer feedback into the grant review process. Instead of the months-long delay between submission and response, digital platforms could allow reviewers to provide iterative comments, allowing applicants to address concerns early. With current timelines, it can take upwards of six months to get comments back, additional months to resubmit, and then another six months to get more feedback.

The Upshot

I’ve seen firsthand the transformative power of the NIH—not just in the breakthroughs that make headlines but in the countless lives quietly improved by both the discoveries it funds and the physicians it empowers with the time and resources to excel as the very best in their fields. This work doesn’t belong to one administration or political party; it belongs to all of us. Science thrives in an environment free from political interference, where bold questions can be asked and unexpected answers pursued. The NIH’s work touches every corner of America—bringing new treatments, improving lives, and offering hope when it’s needed most. To protect its mission is to safeguard the health and well-being of future generations.

Excellent article!

If you put ME/cfs on the graph of NIH funding vs disease burden, Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/cfs that affects millions in US would be very underfunded. NIH needs to stop discriminating against ME and fund at least $100M/yr. Reference: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32568148/