What the President's Agenda Means for the NIH

The President has outlined a plan to significantly scale back NIH funding along with major restructuring. What will this mean for America and the scientific community?

Earlier this year, the White House released its FY 2026 Budget Brief. What hasn’t been making headlines lately but should be is the staggering proposed cut to NIH’s discretionary funding. The agency’s budget authority would drop from roughly $44.5 billion in FY 2025 to $27.5 billion in FY 2026. That’s nearly a $17 billion reduction—or about 40% less money for the largest public funder of biomedical research in the world. The administration has framed this shift as a recalibration toward “essential research at a more practical cost,” along with a push for “gold standard science” and “radical transparency.” But no matter how you spin it, this would be the steepest cut in NIH history.

Yes, this is a budget discussion. But where we choose to spend our money also reflects our values as a nation. It’s about what kind of country we want to be. Do we still believe in investing in discovery? When we put a man on the moon in 1969, we still did. We wanted to lead the world in innovation. We wanted to develop the treatments and cures of tomorrow. And we have. Mortality from heart disease has plummeted over the past 50 years. Life expectancy from many cancers has doubled or even tripled. Are we ready to walk away from all of that?

To put the proposed NIH cuts into context, I’ve included a figure adapted from congress.gov, showing both actual and inflation-adjusted NIH funding over time. You’ll notice something important: while the nominal budget has steadily grown since the 1990s, the inflation-adjusted budget has stayed relatively flat. In other words, even without a cut, the purchasing power of NIH dollars hasn’t kept pace with the cost of doing science.

The standard “R01” award has also been capped at $500,000 per year for more than two decades, despite sharp increases in labor, supplies, and infrastructure costs. That means labs today are doing more with less, stretching resources thinner and thinner.

To understand why these cuts are so alarming, it helps to know just how difficult it already is to secure NIH funding—even before Trump-era proposals entered the conversation. According to NIH’s own data, only about 20% of new R01 applications get funded. Renewals fare a bit better, with a success rate around 40%. At first glance, those numbers might not sound catastrophic. But when you look under the hood, the reality is far more precarious.

Most academic researchers are expected to fund at least 60% of their salary through external grants, and some need as much as 100%. A standard R01 grant typically covers no more than 30-35% of a researcher’s effort, so staying afloat often requires holding two active grants at once. And with only a 1 in 5 chance of success, that means writing and submitting three or more full R01s each year, or one for every NIH cycle.

And that’s assuming you already have the preliminary data. Preparing a single competitive R01, even with existing results in hand, often takes 80 to 150 hours or more. This time comes on top of running a lab, mentoring trainees, teaching, and publishing.

Now imagine what happens if the success rate drops to 12%—which is not a hypothetical, but the likely outcome of a 40% budget cut. At that rate, a researcher would theoretically need to submit five full R01s per year just to maintain their lab. That’s not only unrealistic, it’s impossible. There simply aren’t enough hours in the day, or people on staff, to sustain that kind of grant churn.

Make no mistake, we will lose people. Talented scientists will leave the system, not because they lack good ideas or rigorous data, but because the system will no longer be able to support them. And once that expertise is gone, it won’t be easy to get back.

Indirect Cost Cuts

Another major change buried in the President’s FY 2026 Budget Brief is the proposal to continue capping indirect cost (IDC) rates at 15% for NIH grants. If you’re not steeped in research infrastructure, this might sound like a technical detail. But for anyone working in an academic medical center, this is a red alert. Indirect costs are what keep the lights on, literally. These funds cover the facilities where research happens (labs, offices), the IT and utility systems that support them, and the administrative infrastructure needed to manage grants, ensure regulatory compliance, and oversee safety protocols. These are real and unavoidable costs, but they aren’t allowable as direct charges on most NIH grants. Without a mechanism to recover them, institutions are left footing the bill.

That’s why the proposal to cap IDCs at 15% has been so contentious. Most research institutions currently receive rates closer to 50–60%, based on negotiated agreements with the federal government. A hard cap would mean institutions lose money on every grant they accept. Over time, this would decimate the academic research enterprise.

In the meantime, a coalition of ten organizations—known as the Joint Associations Group, representing research universities, academic health centers, and other stakeholders—has put forward a counterproposal. Their plan would give institutions the option to either include a portion of these costs within the total project budget or receive a fixed percentage of the overall award to cover infrastructure. Sen. Susan Collins (R-Maine) has voiced early support. This is more than an accounting issue. It’s a fight over whether the federal government is willing to pay for the full cost of the science it claims to support. You can read more here.

Overall Restructuring

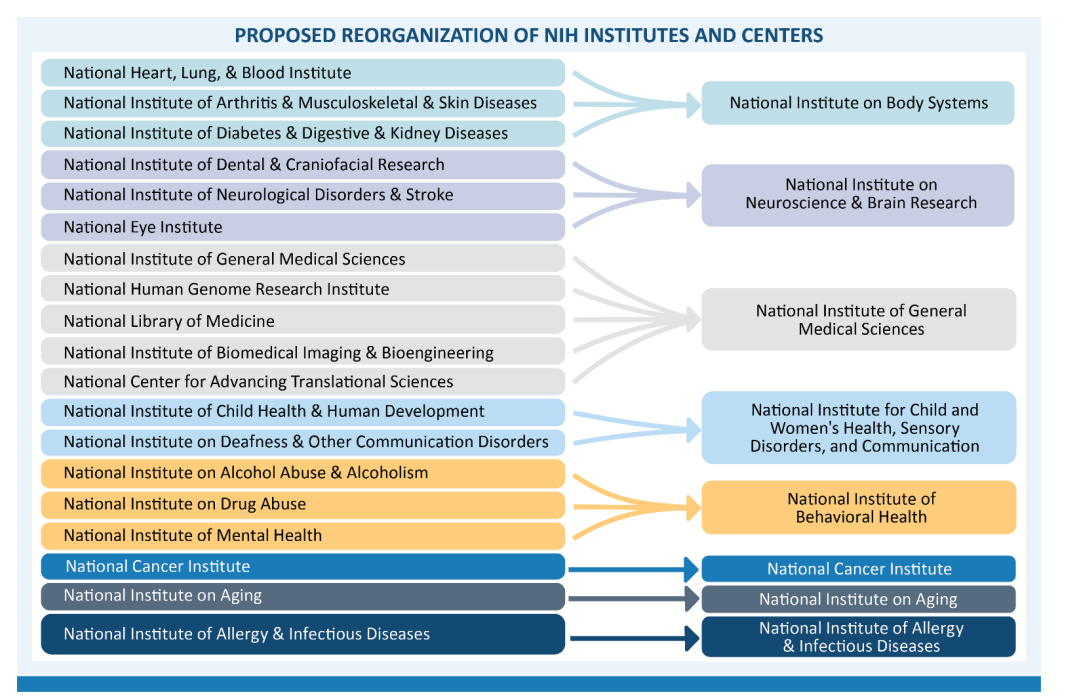

In a separate FY 2026 Budget Brief for HHS, a comprehensive reorganization aimed has also been proposed. For NIH specifically, the budget calls for a leaner organizational structure that focuses on “gold standard science” and “radical transparency,” while investing in security infrastructure. The impact of this approach can be seen in this proposed reorganization. How much of the existing structure and staff from the current institutes would be retained is unclear. Concerns from investigators in the various arenas center around whether this will translate to less focus on specific diseases (and ultimately the patients they represent).

This is what has researchers worried. Disease-focused institutes such as the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Institute of Mental Health play a vital role in setting priorities, supporting investigator communities, and sustaining long-term commitments to patient populations. If those structures are flattened or absorbed into larger administrative units, will rare diseases, for instance, get left behind? Will community engagement and patient advocacy have a seat at the table?

Right now, we don’t have clear answers. What we do know is that restructuring on this scale will likely create disruption before efficiency, and in science, lost momentum is hard to regain.

Switch to a Multiyear Funding Model

Also tucked into President Trump’s FY 2026 budget is a proposal to shift up to half of all NIH research grants to a multi-year funding model—meaning investigators would receive the full amount of a multi-year award up front, rather than in annual installments. While this approach offers stability and reduces red tape, when bundled with a proposed 40% cut to NIH’s overall budget, this could even more dramatically shrink the agency’s capacity to fund new science.

Under the current system, most of NIH’s budget is already committed to prior multi-year grants. Only about a quarter, the so-called “churn,” is available each year for new awards. Fully funding more grants up front without a transitional cash infusion would drain that pool even faster. STAT news reported that according to the administration’s own projections, total research grants would fall from 42,143 in 2024 to just 27,477 in 2026, while new awards would drop by more than half, from 10,086 to 4,312.

Critics warn this combination amounts to a backdoor cut. “If you keep the budget flat and move a significant portion of the portfolio from annual dollars to front-loading, it’s a 30–50% de facto cut,” said Adrienne Hallett, former NIH legislative director. While the White House frames the change as a move toward efficiency and rigor, it’s hard to square that with such a sharp contraction in how many projects can be funded. In practice, this shift could stabilize funding for a few while at the same time collapse funding for the many.

The Upshot

This isn’t just rebudgeting. This is a redefinition of what the NIH is for and who it serves. A 40% reduction in NIH’s budget, paired with multi-year grant payouts and a cap on indirect costs, doesn’t just shrink the number of projects. It shrinks the pipeline of scientists, the scope of ideas, and the possibility of breakthroughs that change lives. It puts fewer diseases in the spotlight. It leaves more patients waiting.

I also think about what this means for us as a nation: a step away from the kind of ambition that has long defined American science. For decades, NIH has been more than a funding agency. It has been a symbol of our belief that knowledge saves lives and that discovery is worth investing in.

When we put a man on the moon in 1969, it wasn’t because it was cost-effective. It was because we wanted to lead. It was about national purpose, and the belief that progress, not just profit, was a public good. NIH has always been part of that same story. So the question now is not just whether we can afford these cuts. The question is whether we still believe in that story. If we walk away from NIH, we’re not just losing infrastructure or grants. We’re walking away from patients, global leadership, and the economic engine that medical innovation has long provided. I’ll be honest, I don’t understand when we stopped caring. I along with many other scientists still deeply believe in this mission. But this I do know. If we don’t speak up now, we may not get the chance to rebuild what we have lost.

An alternative viewpoint.

We, as collective stewards of the government/NIH largesse, have not only been bad at money and personnel management, but we’ve allowed common criminals, fraudulent actors, censors, and grifters (e.g. : Former Dean USC-Keck SoM, current Dean of SoM UCLA , Former Department Chair Stanford Department of Medicine, former President of Stanford respectively) to ascend to the roles that are most cherished in our profession.

That has denigrated not only our profession, but has provoked a (deserved) public backlash.

And let’s be clear about the accomplishments that you cite of the research enterprise.

Most of those are NOT attributable to administrative leaders within our profession. In other words, there’s a significant chasm between what constitutes “scientific success”, versus success in life.

It seems that being successful in life within the context of medical sciences requires a transition out of science, and that’s at the crux of the lamentations you write about.

Raj K Batra.