Vaccine Questions, Honest Answers: How the National Debate is Shaping Patient Decisions

RFK's confirmation hearings, vaccine safety and how our conversations about vaccinations have changed since the COVID-19 pandemic.

On November 14, President-elect Donald Trump announced that he had selected Robert F. Kennedy Jr. to lead the Department of Health and Human Services. Reactions were swift and deeply divided. These conversations continue in doctor’s offices across the country. In the years before the pandemic, vaccine skepticism lingered in the margins, but the vast majority of parents still vaccinated their children against measles, mumps, and polio without much fanfare. But almost like declaring a preference for coffee over tea, patients now express their stance without expectation for discussion—I’ll take flu or RSV, but not COVID. Oh no, I don’t do vaccines. I’ll take anything, as long as it’s not mRNA. It’s not up for debate, not something they feel the need to justify. It’s just who they are. While vaccine hesitancy existed before the COVID-19 pandemic, this is a fundamental change.

The roots of vaccine hesitancy trace back decades—to flawed studies, fear-driven misinformation, and broader distrust in institutions. But the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated these trends, with vaccines becoming as much a political symbol as a public health measure, risking decades of progress in infectious disease prevention. In this article, we break down the science of vaccines, the rise of modern vaccine skepticism, and what’s at stake when misinformation gains a foothold.

Vaccines: A Public Health Triumph

Vaccines have saved countless lives, with immunization efforts dating back to the 15th century. Jonas Salk’s polio vaccine (1950s) nearly eradicated polio, a testament to rigorous research, strategic implementation, and public trust in science.

Vaccines teach the immune system what to expect so it can be prepared to fight back. There are different types of vaccines, each designed to train the immune system in a specific way:

Live-attenuated vaccines contain weakened versions of a virus or bacterium, offering long-lasting protection after just one or two doses (e.g., measles, mumps, rubella, and chickenpox vaccines).

Inactivated vaccines use killed pathogens and typically require multiple doses to build and maintain immunity (e.g., flu and hepatitis A vaccines).

mRNA vaccines provide genetic instructions for the body to produce a harmless viral protein, enabling the immune system to mount a targeted response (e.g., COVID-19 vaccines).

Vaccination isn’t just about individual protection—it’s about community defense. When enough people are immunized, diseases struggle to spread, safeguarding those who are too young or medically unable to be vaccinated. This concept, herd immunity, is crucial for specific diseases but impossible for others. Herd immunity thresholds vary by disease, depending on how contagious the pathogen is.

For measles, one of the most contagious diseases, approximately 95% of the population needs immunity to prevent outbreaks. From a historical perspective, it’s helpful to see how vaccinations have protected public health, as can be seen by this data from the CDC.

However, in the US, we saw decreases in the rates of routine vaccinations for kindergartners during the 2020-21 and 2021-22 school years after having held steady for a decade. Importantly, vaccination rates did not return to pre-pandemic levels during the 2022-23 school year. That same year, exemption rates rose in 41 states, with ten states reporting exemption rates over 5%. Over 93% of those exemptions were nonmedical.

The U.S. no longer consistently achieves the 95% immunity level necessary for measles herd immunity, which provides the opportunity for outbreaks. In 2019, we saw the largest outbreak of measles in the U.S. since 1992, which occurred in a New York City community with a cluster of unvaccinated children.

COVID-19 Vaccines: A New Chapter

Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic didn’t just ignite vaccine hesitancy — it supercharged it. The rapid development of COVID-19 vaccines seemed miraculous but was, in reality, decades in the making. Researchers like Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman had long refined mRNA technology and lipid nanoparticle delivery, a once-overlooked approach that became the foundation of Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines. The FDA’s record-speed Emergency Use Authorization was possible only because of years of groundwork by scientists, public health officials, and pharmaceutical teams.

Yet concerns about the speed of COVID-19 vaccine development, new technology, and EUA fueled hesitancy. The novelty of COVID-19 vaccines led to public skepticism, particularly regarding their safety. COVID-19 vaccines remain highly effective at preventing severe illness and death, with efficacy ranging between 73.5%–95.2% in real-world populations. For context, flu vaccines, which have been used for decades, typically reduce the risk of flu-related doctor visits by 40–60% when the vaccine matches circulating strains. Even with moderate effectiveness, vaccines can still prevent millions of illnesses, hospitalizations, and deaths annually.

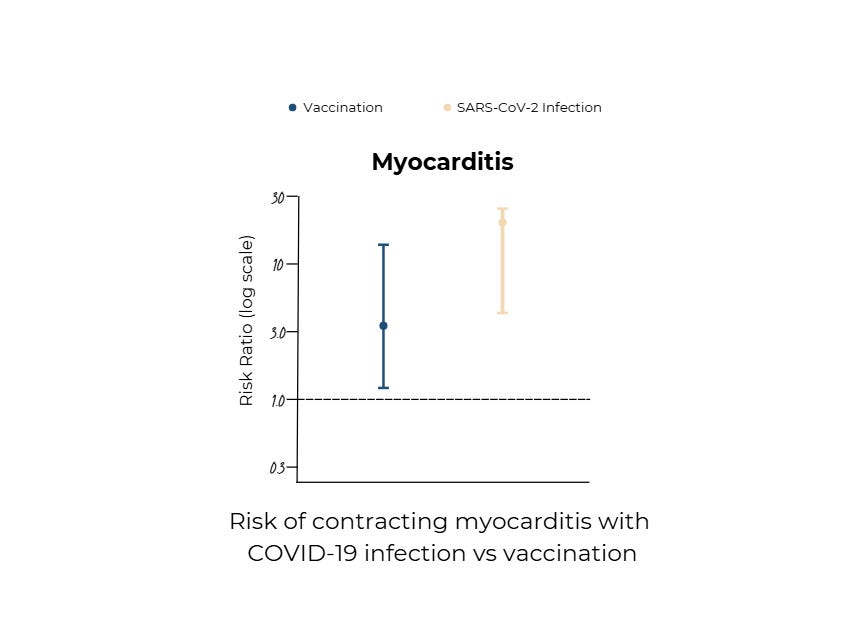

While concerns about side effects from COVID-19 vaccines have garnered attention, it's crucial to understand that these adverse events are still exceedingly rare and generally mild. However, the incidence of side effects is still significantly lower than the risks associated with contracting COVID-19. For example, this study published in the New England Journal of Medicine demonstrates that myocarditis occurs more frequently after a COVID-19 infection (11 persons per 100,000 persons infected) than after vaccination (3 persons per 100,000 persons vaccinated — see graph, adapted from that article). The benefits of vaccination in preventing severe illness, hospitalization, and death still outweigh the risks of side effects.

Ultimately, extensive post-marketing surveillance and global safety monitoring continue to confirm that the benefits of COVID-19 vaccination far outweigh the risks. The vaccines have been administered to billions of people worldwide, with rigorous data collection reinforcing their safety and effectiveness. While open conversations about risks are necessary, it is equally crucial to contextualize these risks against the dangers of the disease itself—ensuring that fear does not overshadow fact.

Addressing Common Vaccine Misconceptions

The myth that vaccines cause autism remains one of the most damaging misconceptions in modern medicine. It originated in 1998 with a now-retracted study by Andrew Wakefield, whose research was later exposed as fraudulent. Despite overwhelming evidence disproving his claims, the fallout continues to fuel vaccine hesitancy. Large-scale studies from the CDC, NIH, and the Institute of Medicine, examining millions of children, have found no link between vaccines and autism. Autism is a complex neurodevelopmental condition with strong genetic and prenatal influences, yet misinformation persists. The consequences are real: preventable outbreaks of diseases like measles have surged in communities where vaccine refusal has taken hold.

Concerns over vaccine ingredients have long played into public fears, often driven by scientific misunderstandings. Aluminum salts, for example, have been used safely in vaccines for over 70 years to enhance immune response, yet they are frequently vilified. The reality is that the amount of aluminum in a vaccine dose is minuscule compared to what we ingest daily through food and water.

The debate over natural immunity versus vaccine-induced immunity has gained new urgency in the wake of COVID-19. Some studies suggest infection-induced antibodies can last up to 20 months, but natural immunity is highly unpredictable. The notion that widespread COVID-19 infection could have provided a shortcut to herd immunity proved dangerously misguided. With COVID-19, waning immunity, viral mutations, and the unpredictable nature of infection-induced protection meant that mass infection was never a viable public health strategy. For COVID-19, this strategy also assumes a high number of deaths required to reach herd immunity is acceptable. To date, over seven million individuals have died from COVID-19.

The Rise of Vaccine Hesitancy

Trust isn’t lost overnight. It erodes. COVID didn’t create vaccine hesitancy, it just exposed how deep the cracks already were. Over the past two decades, significant events like the Iraq War, the 2008 financial crisis, and the COVID-19 pandemic have deepened public skepticism toward institutions. During the pandemic, shifting health guidelines, media sensationalism, and political polarization left many feeling misled. Public health messaging changed frequently—sometimes necessarily, sometimes clumsily—creating an environment where even well-intentioned people questioned official guidance.

The pandemic also coincided with an explosion of misinformation online. Vaccines have also increasingly become tied to political identity, with acceptance or rejection often aligning with party lines. I've cared for patients who find themselves at war with different facets of their own identity—like a healthcare professional who trusts the science behind vaccines yet struggles to reconcile that conviction with the political ideology that shapes their worldview.

The media also amplified every alarm, then quietly backtracked. The result? A public that no longer knows whom to believe. Social media has only worsened the problem, spreading exaggerated claims about vaccine risks faster than scientific explanations. A single misleading TikTok can reach millions, while fact-checks struggle to gain traction. Well-meaning stories about rare side effects become fuel for widespread fear, distorting risk perception. The result is not just vaccine skepticism but a growing reluctance to accept public health recommendations at all.

Another challenge is complacency. Ironically, the success of vaccines has contributed to their own skepticism. Many now believe certain diseases—measles, polio, even COVID-19—are mild or no longer a serious threat. Others place their faith in “natural immunity,” assuming it offers better protection than vaccines. These beliefs ignore the reality that widespread immunization is what keeps these diseases in check. When vaccination rates drop, outbreaks return.

A Contentious Confirmation

Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s second confirmation hearing on January 30th exposed deep divides over vaccine skepticism. Democrats hammered his record—Senator Maggie Hassan grew emotional discussing her son with cerebral palsy, while Senator Angela Alsobrooks condemned Kennedy’s claim that Black Americans should follow a different vaccine schedule.

Some Republicans, like Rand Paul and Tommy Tuberville, defended Kennedy, while Lisa Murkowski expressed doubts. Senator Bill Cassidy’s vote may be decisive, pressing Kennedy on how he would use the public’s trust. Cassidy, a physician himself and a Republican from Louisiana, serves as the chair of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions. Cassidy expressed reservations about Kennedy's past anti-vaccine statements, stating he was "struggling" with the nomination due to concerns over Kennedy’s prior record and whether he would really work “To improve the health of Americans, or to undermine it.” Whether Kennedy will be confirmed remains to be seen.

The Upshot

Vaccine hesitancy has never been just about the science, it’s really about trust. For many, skepticism isn’t a rejection of facts but a response to institutions that feel distant, inconsistent, or dismissive. People aren’t just questioning vaccines; they’re questioning the systems delivering them.

Restoring trust won’t come through mandates or marketing campaigns but through human connection. While many distrust institutions, they still trust their doctors. Real change happens in one-on-one conversations—where people feel heard, their concerns acknowledged, and their questions answered with empathy.

Admittedly, these conversations aren’t easy. I still struggle with them myself. But I believe trust can be rebuilt. Not just in exam rooms but at kitchen tables, in the quiet moments where people feel seen. Misinformation thrives where we have failed to connect. The challenge now isn’t just fighting bad information—it’s earning back belief in the system itself.

Decreasing vaccination rates are very concerning.

Covid is a respiratory vascular disease process immunological shielding comes from "normal" vascular glycocalyx nanobubble gas exchange physiology. There is is wrong and missing physiology in medicine so that putting vaccines at forefront of attacking Covid while not understanding that physiology was and still is a complete red herring. Dexamethasone treatment which improved things was the main clue clinically. Ref Ninham papers